THE ORIGIN OF 420

- Bobby Black

- Apr 10, 2023

- 13 min read

This month, stoners around the world will be celebrating our high holiday – April 20th, a.k.a. 4/20. But how exactly did "420" become the official number of cannabis? Over the years, there have been several myths circulated: that it was some police code related to weed, or that it’s the number of chemical compounds in the plant ... but believe it or not, the ultimate marijuana meme was actually started over 50 years ago by a group of teenagers in Marin County, California known as The Waldos.

MEET THE WALDOS

The story of 420 begins in 1970 at San Rafael High School with a group of five stoner buddies – Steve Capper, Dave Reddix, Jeffrey Noel, Larry Schwartz, and Mark Gravitch – who, due to their penchant for hanging out at a particular wall, came to be known collectively as “The Waldos.”

“In the middle of campus, there’s a wall in the lunch quadrant right against the main building,” explains Waldo Dave. “We would meet there almost daily, hang out, do impressions of people walking by, and try to crack each other up.”

Eventually, these “comedic desperados” grew bored hanging out at school and decided to start venturing out in search of kicks.

“We were getting tired of this Friday night high school football scene and going to parties," says Waldo Dave. "We wanted to meet strange and interesting people and do weird things, so we started going on these things we called “safaris.”

The safaris were random, weekly expeditions that The Waldos would undertake together around the greater Bay Area. They’d all pile into Waldo Steve’s green ‘66 Impala (a.k.a. the Safari Mobile), crank up some New Riders of the Purple Sage, Santana, or Bob Dylan on the eight-track, fire up a few joints, and hit the road in search of adventure. When it came to a Waldo Safari, there were only two rules: They had to be going somewhere new and they had to be stoned.

“We’d challenge each other to come up with some new, unusual thing to do every week. We did some dangerous things.”

Their safaris included climbing out onto the girders underneath the Golden Gate Bridge and jumping around in the nets like they were trampolines, infiltrating Hamilton Air Force Base James Bond-style, and showing up unannounced at a holographic lab in Silicon Valley.

“I was reading an article [in Rolling Stone] about the very first people who were developing holograms down towards Silicon Valley,” Waldo Steve recalls. “It said that they had built an entire holographic city. We couldn't even imagine anything like that. In 1971, three-dimensional images made out of laser light … that was like Star Wars!" [Coincidentally, Star Wars was created right there in Marin County about half an hour from their school, but wouldn't actually be released until 1977].

"I'm thinking, well, screw the football game—I gotta check that out!" he continues. "So the next week we all went down, got high, and met and hung out with the scientists. We had them laughing and hugging us and inviting us to come back. And that was our first safari.”

But among all of their unusual adventures, it was one safari in particular involving a would-be treasure map that first planted the seed for the term “420.”

STONER SAFARI

One day in the fall of 1971, a classmate of theirs named Bill McNulty approached Waldo Steve with an intriguing opportunity: he claimed that his brother-in-law, who was in the Coast Guard Reserve stationed out at the Point Reyes lighthouse, had planted a clandestine patch of weed somewhere on the Peninsula, but had grown suspicious that officers were on to him and that he might get busted. Heeding his paranoia, he’d decided to abandon the garden and offer someone else the opportunity to go harvest it for themselves using the crudely drawn map that McNulty was now giving them.

A treasure map leading to a secret weed garden? Naturally, this was an offer The Waldos couldn’t refuse.

“Surely this is the ultimate safari,” Waldo Steve told Freedom Leaf magazine in April 2015. “No more adventurous nor nobler quest could be devised by the mind of man.”

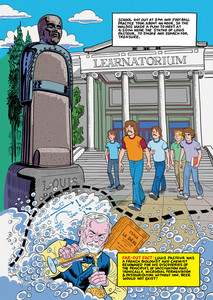

Eager to embark upon their expedition, they made a plan to head out later that very day after school. Their classes ended at 3:00 pm, but Waldo Jeff and Waldo Larry had football practice afterward that would last about an hour, so they decided to all meet in front of the school at the statue of French chemist Louis Pasteur at—you guessed it—4:20 pm.

So at 4:20, they got high at the statue, then headed out to Point Reyes (about an hour west of the school) with map in hand to search for the weed. Sadly, they didn’t find it, but vowed to keep looking. They ventured out almost daily for weeks, each day reminding each other about their afterschool plans using the new code they’d developed.

“We’d see each other in the hallways during the day, and we’d smile and say, “Four twenty, Louis,” Waldo Steve explains.

To which Waldo Dave jokingly adds, “Louis is actually the sixth Waldo.”

COVERT CANNABIS CODE

After many weeks, the Waldos eventually gave up their search. But though they never found that herb garden, what they’d gained would prove to be far more lasting and valuable: after dropping the “Louis,” they had a new clandestine code for cannabis: 420.

“We realized we had a secret code we could use to talk about weed in front of our parents, cops, teachers ... whoever.”

At a time when a single joint could get you a decade in prison, a secret code for weed was a useful thing indeed—especially for a group of guys who loved getting stoned as much as they did.

“Smoking and scoring were always on our minds, so we were constantly paranoid, looking over our shoulders for cops," Waldo Steve attests. "Is there gonna be one seed on the floor that's gonna get you busted? And the consequences were very real.”

As if avoiding cops weren’t bad enough, Waldo Jeff’s dad was actually one of the highest-ranking narcotics agents in Northern California—making huge busts that sometimes even included Hollywood celebrities.

“His dad used to bring home all kinds of samples from the busts he made and kept them in his trunk. Jeff would get the keys to his car, get some of the weed and we'd smoke it," recalls Waldo Dave. "One time, his dad caught us smoking at a little garden shack behind the house, and [Jeff] really paid a price for that. His dad was a nice guy, but he was afraid he could lose his job and his reputation because of his son. And Jeff said he was always trying to figure out what 420 meant, but he never figured it out.”

THE DEAD CONNECTION

Unlike Jeff’s dad, Waldo Mark’s dad was a real estate broker – a fact that would play a huge role in helping 420 spread beyond their small circle and out into the counterculture at large. You see, as it turns out, one of his dad’s biggest clients was none other than The Grateful Dead.

“The Grateful Dead had a big organization based in San Rafael,” says Waldo Steve. “They needed office space, rehearsal space, places to store equipment ... Mark’s dad found them all those places.”

Mark’s dad wasn’t The Waldos’ only connection to the Dead, though – Waldo Dave’s brother Patrick also happened to be good friends with bassist Phil Lesh.

“In 1975, the Dead were on hiatus from touring, and Phil started a couple of side bands: Too Loose to Truck and Sea Stones," Waldo Dave recalls. "Phil asked Pat if he could manage the two bands, and Pat said sure… and then hired me to be a roadie.”

Thanks to these relationships, the Waldos got to hang out with members of the Dead quite a bit—often taking care of their homes and pets for them while they were out on tour, and hanging out with them at their shows.

“I was backstage a lot of the time with these guys like Phil [Lesh], David Crosby and Terry Haggerty—getting high and using the term 420, and they were all kind of chuckling at it and thought it was cool.”

Soon others on the scene picked it up and it started spreading throughout the Deadhead community, where the phrase started spreading like wildfire. The code also trickled down to the next generation of students at San Rafael High, who began holding their own celebrations on April 20th throughout the 1970s and 80s – including one at the top of Mt. Tamalpais (one of The Waldos' favorite smoke spots).

“Our younger brothers, friends, and family members, they all picked up on it," says Waldo Dave. "It was a generational thing that went from class to class—it became a thing where the heads were proud to be part of 420 history in the later years.”

In 1990, a flier for that gathering on Mt. Tam (one that explained, albeit incorrectly, the meaning of 420) was making the rounds at Grateful Dead concerts around the Bay Area. It was in the parking lot of one such Dead show in Oakland that this flyer found its way into the hands of someone perfectly positioned to amplify 420’s exposure—an editor at High Times magazine.

HIGH TIMES

During the last days of 1990, High Times news editor Steve Bloom was hanging out on Shakedown Street at one of the Dead’s New Year’s Eve shows at the Oakland Coliseum when he was handed a half-page handbill promoting the 4/20 gathering atop Mt. Tam and explaining, albeit incorrectly, the origin of 420. Bloom was so intrigued by the flyer that after returning to the HT offices in NY, he transcribed and published the text of the flyer in the May 1991 issue.

Over the next several years, 420 made several more appearances in the magazine: repeatedly popping up in the Hemp 100 (an illustrated list of 100 different reader-submitted items in the back of every issue), and in an article by freelancer Brian Jarvin in the May 1997 issue.

The HT staff adopted the term internally, as well—making it a point to head out to the back stairwell for a smoke at 4:20 each day (like we really needed an excuse!), and holding small celebrations on April 20th. In a 2019 article for Freedom Leaf magazine, Bloom recalls one such gathering:

“I remember one April 20th when we decided to go down to Union Square – which was a few blocks from the office. About 20 of us went there and celebrated 4/20 by passing joints under picnic tables. New York City was the marijuana arrest capital of the world. This was pretty daring at the time.”

[For the record, I’m pleased to confirm that I was among those High Times staffers in attendance!]

The 420 flyer and its message were also spread by the Berkeley-based activist organization CAN (Cannabis Action Network), who took it on the road with them to various cannabis events and music festivals (such as Lollapalooza, H.O.R.D.E., and the Warped Tour) throughout the 1990s. By the end of the decade, The Waldos were seeing the number everywhere: carved into trees and benches, spray-painted onto walls and signs, and of course in the multitude of merchandise and media that predictably started springing up—including t-shirts, hats, songs, and albums. Each time one of the Waldos would see 420 somewhere, they’d get a kick out of sharing with the others—as if they were all part of some secret stoner scavenger hunt.

At first, The Waldos were reluctant to come forward and claim it—fearing possible backlash due to cannabis’ continued illegality. But eventually, as cannabis became less taboo and 420 became more pervasive throughout the counterculture, they decided it was time for them to take credit for the phenomenon they’d started. So in 1998, Waldo Larry reached out to the company 420 Tours (a cannabis travel company that was working with High Times on events) about it, who then redirected him to the magazine’s editor-in-chief Steve Hager. After hearing Larry plead his case, Hager agreed to fly out to San Rafael and meet with them and investigate.

“He came out one weekend in Spring 1998 and hung out with us,” said Waldo Dave. “We showed him all our proof, and drove him to all the places we used to hang at, which we called our “offices”—all the scenic spots where we got high, like up on the top of Mt. Tam, down at Lake Lagunitas, even out to Point Reyes."

After spending a few days with The Waldos and seeing their evidence (more on that in a minute), Hager was convinced they were the real deal. After returning to New York, he wrote a one-page article entitled “420 or Fight” (December 1998) — the first time their story had ever been published.

“Hager went back and wrote his article, and then he went right onto ABC News and proclaimed us the creators of 420,” Waldo Dave remembers. “And that was the beginning of everything.”

PROOF VS. PRETENDERS

After that, the floodgates had been opened. Soon media outlets from around the country began covering the Waldos: A front-page article in the LA Times, an investigation by the Huffington Post ... hundreds of interviews and articles were published about 420 and its originators.

Meanwhile, 4/20 gatherings around the nation were growing larger and more numerous— particularly on college campuses such as the University of Santa Cruz and the University of Colorado Boulder, which attracted around 20,000 attendees.

“The police were helpless to control that, so they just let it go, and everybody got a taste of what freedom would be like for people to smoke together and have a good time without the fear of getting busted,” Waldo Steve says. “And of course, the mainstream media started paying attention to these huge gatherings, and this all of a sudden created a forum for all of them to start talking about marijuana legalization. So in a way, 4/20 was kind of a catalyst to the end of prohibition.”

Of course, being in the spotlight often draws unwanted attention. After The Waldos went public about being the creators of 420, there was a bit of a backlash; suddenly, a cadre of haters and imposters began coming out of the woodwork claiming that it was they, not The Waldos, who had created 420. Among the would-be usurpers was a group of The Waldos’ former San Rafael classmates who called themselves “The Bebes.” In October 2012, the online pot publication 420 Magazine posted an article about The Bebes in which they essentially accused the Waldos of ripping the idea of 420 off from them. The following April, Waldo Dave posted a detailed rebuttal on the Huffington Post laying out all of the evidence (unlike The Waldos, The Bebes have never presented any actual evidence to back up their claims).

“All these people saying, ‘Oh, we started this’ – they’re full of shit,” Waldo Dave states. “None of them have a shred of proof to their claim.”

So what proof do The Waldos have to back up their claim? Quite a bit, it turns out:

They have a copy of the San Rafael High School "Red and White" newspaper from 1974 with a reference to 420, as well as several postmarked letters from the early 1970s between Waldo Dave, Waldo Steve, and their friends Ken Blumenthal and Patty Young that all contained references to 420.

“I wrote Steve a letter in the mid seventies, and I told him about being a roadie for Phil Lesh's bands and getting high with Crosby and Lesh,” Waldo Dave recalls. “And I rolled up a doobie, smashed it down flat and put it in the letter and sent it to him off in college with the words 'a little 420 enclosed for your weekend.'”

And perhaps coolest of all, they have a tie-dye-style batik flag emblazoned with both a pot leaf and the number 420 made for them by their friend Patty in her arts and crafts class back in 1972, along with the school records to back up its origin.

They keep all of this evidence in a safe deposit box inside the vault at Wells Fargo bank world headquarters in San Francisco—located at, I shit you not, 420 Montgomery Street.

Indeed, The Waldos have gone to great lengths to verify the authenticity of their claim. They even hired a private detective to track down that Coast Guard reservist who allegedly planted the patch and drew the original treasure map.

“One thing [The Bebes] said was, ‘There was never any Coast Guardsman — The Waldos never went out to look for that weed,’" recalls Waldo Steve. "And at that point, I was like, ‘Well, screw that!’ and I went on a mission to go find the Coast Guardsman.”

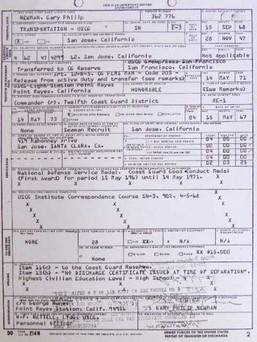

In 2016, after six years of searching, they finally found him—the original creator of the map and former Coast Guard reservist, Gary Newman. Newman, then 86 and homeless in San Jose, confirmed the whole story—even granting them access to his military records to prove he was stationed at Point Reyes at the time, and accompanying them there to try (unsuccessfully) to identify where the garden had been.

"We contacted his brother-in-law, Pat McNulty … and we all got together, went out to Point Reyes, and I shot a little documentary with [them],” says Waldo Dave. "Pat and his brother have both passed since then, but we wanted to make sure this story was on the record so we had him give an affidavit and swear to it, and we have it notarized.”

“We have 166 pages of Coast Guard records to back all this stuff up," add Waldo Steve.

CULTURAL IMPACT

Since being acknowledged as the rightful originators of 420, The Waldos have started their own company and licensed some 420-related merchandise of their own, including a line of glowing 420 watches and a “420 Waldos 1971” vape cartridge (with Oakland-based Chemistry) – donating proceeds from both to the Drug Policy Alliance.

A few years later, they partnered with nearby Lagunitas Brewing in Petaluma to release The Waldos Special Ale: a seasonal triple IPA billed as “the dankest and hoppiest beer ever brewed,” released on—you guessed it—April 20, 2018.

“We personally picked the hops to replicate the dankest marijuana buds you could ever find,” brags Waldo Dave.

What's more, the brewery has given The Waldos lifetime passes for free beer, and even released a little comic book (illustrated by artist James Yamasaki) with the beer that tells the story of 420.

Speaking of cool artists—in 2021, they enlisted legendary Grateful Dead poster artist Stanley Mouse to create a limited edition NFT/poster commemorating the creation of 420.

“Waldo Larry is in the printing business and he knows Stanley Mouse, so he proposed to him, ‘Hey—why don't you make a poster for us and we'll put it up as an NFT?'At the time, Stanley said, ‘You know what NFT stands for? Nothing fucking there!' Waldo Dave chuckles. "But then he reluctantly agreed."

The artwork depicts The Waldos as skeletons cruising along the Point Reyes Peninsula in their Safari Mobile (with Mouse's Grateful Dead logo on the hood) searching for the lost weed patch.

The cultural impact of 420 on the cannabis world cannot be overstated. From television and movie references (like the scoreboard in Dazed and Confused, the clocks in Pulp Fiction, and the many contestant bids on The Price is Right) and stolen mile marker signs to actual legalizations bills and the countless celebrations that go on every day and every year around the globe, 420 has become ubiquitously and irrevocably synonymous with cannabis – and we owe it all to 420’s founding fathers, The Waldos.

Thanks, fellas ... and Happy 4/20, everyone!

For more about The Waldos, listen to the full interview in our Cannthropology potcast below (or wherever you get your podcasts), and visit their website at 420waldos.com.