HASHISH, HAWAII & THE HIPPIE MAFIA

- Bobby Black

- Oct 29, 2020

- 17 min read

Updated: Nov 22, 2020

The life and crimes of Travis Ashbrook—founding member of the Brotherhood of Eternal Love.

When discussing the history of cannabis in America—or drug culture in general, for that matter—it’s impossible to overstate the influence and impact of The Brotherhood of Eternal Love. In the span of just a few short years (1966-1972), this handful of stoner surfer buddies from Laguna Beach had transformed into the largest drug syndicate on earth—dubbed by Rolling Stone magazine “The Hippie Mafia.” Producing and distributing tens of millions of doses of LSD, they were sacred psychedelic warriors on a mission to turn on the world. From Charles Manson to Timothy Leary, the Grateful Dead to Jimi Hendrix, Newport Pop to Altamont…so many iconic aspects of the counterculture connect back in some way to the Brotherhood and the infamous acid they distributed, Orange Sunshine. The Brotherhood’s grand vision was made possible in large part by one of their founding members—and arguably the most notorious hashish smuggler in US history—Travis Ashbrook.

THE BROTHERHOOD BEGINS

As a teenager in Orange County, Travis was making and repairing surfboards out of his parent’s garage while still in high school before eventually opening a small surf shop on Laguna Beach. He smoked his first joint with his buddy Buddha in 1963 and was immediately hooked. He started making regular surf trips down to Mexico and bringing weed back with him. By the age of 17, he was smuggling kilos back from Tijuana into Tecate every weekend and selling them to other dealers—such as a local acid connection known as The Witchdoctor. It was at Witchdoctor’s place up in Seal Beach in 1964 that Travis reconnected with a fellow teen pot dealer named Johnny Griggs.

Part of a local hotrod gang called the Street Sweepers, "Farmer John" Griggs was a notorious boozer, brawler, and heroin user. But after robbing a stash of LSD from the home of a Hollywood producer, he tripped out for the first time and had a spiritual epiphany. Overwhelmed by his experience of "God-consciousness,” Griggs returned the stolen acid, gave up his gangbanger ways, and devoted himself to proselytizing on behalf of LSD. He began taking small groups out into the woods every Sunday and leading them on guided trips. Travis had also experienced “death of the ego” moments while tripping before, but it wasn’t until he accompanied Griggs on these excursions that he began to find meaning in the experience. Believing that LSD was the ultimate tool for human enlightenment, Griggs—along with his wife Carol, friends Michael Randall, Ricky and Ron Bevans, Chuck Mundell, Travis, and a number of others—made it their sacred mission to turn on the world. They decided to form a new religion dedicated to truth, love, peace, and oneness for all, which Mundell christened “The Brotherhood of Eternal Love.”

On October 26th, 1966 (just 20 days after California became the first state to make LSD illegal) the Brotherhood incorporated themselves as a non-profit, then rented an old stone house in Modjeska Canyon and made it their church. Before long they were cranking out their own acid, and Griggs’ trip sessions had expanded into groups of 50-100 people.

In the fall of 1967, at the urging of guru friend Richard Alpert (a.k.a. Ram Dass), they rented a storefront at 670 South Coast Highway and opened a huge psychedelic emporium—selling books, hippie clothing, drug paraphernalia, and health food, as well as offering a juice bar, meditation room, art gallery and more. Mystic Arts World, as they called it, quickly became the biggest headshop in SoCal–earning it the nickname “Haight Ashbury South.”

With hordes of hippies moving into the area, they soon took over a small neighborhood off Laguna Canyon Road which Griggs nicknamed Dodge City. Dodge City became such a psychedelic hotspot that in Winter 1967, Griggs even persuaded acid’s patron saint himself Timothy Leary to come live there with them.

The Brotherhood’s plan was never to get rich from selling acid, but rather to facilitate an evolution of human consciousness by giving it away to as many people as possible. But to turn on the masses, they’d need to produce hundreds of millions of hits of acid—and to do that, they’d need money. The best way to fund their revolution, they decided, was by smuggling marijuana and hashish. That’s where Travis came in.

“I was the hash guy,” Ashbrook attests with a smile. “That was my thing.”

THE HASH GUY

Travis first fell in love with hash during his high school days at the Golden Bear—a famous bar in Huntington Beach where surf guitar king Dick Dale used to perform. From 1963-65, Travis worked there as a stage manager and drug dealer to the musicians (he turned The Monkees’ Peter Tork on to acid). Like LSD, hashish was scarce and expensive in the mid-1960s—a problem he hoped to rectify.

“I was always looking for it…you just couldn’t find it anywhere,” laments Ashbrook. “So I finally got to thinking, you know what? Let’s just go get some of this for ourselves!”

After a bit of research, he hatched a bold plan: fly to Europe, buy a car, drive to Istanbul, fill the door panels with hash (as he did with weed back in Mexico), and ship the car back home. He raised $5000 from the crew and he and fellow Brother Ricky Bevans took off on their hashish hunt. In winter 1967, they booked a flight from LA to NY, then an Icelandic Air prop plane to Luxembourg, then a train to Munich where they bought a brand new Ford Taunus for $500 and hit the road for Turkey: up through the Alps into Austria and down through Yugoslavia. Just before crossing the border into Greece, they picked up a hitchhiking hippie couple. While sharing a joint, they told the couple of their plans and were offered a bit of advice.

“You don’t want to get your hash in Turkey—the stuff’s not that good and it’s expensive,” the hitchhiker cautioned them. “You wanna go to Afghanistan. Don’t even bother to score any hash until you get to Kandahar—get it there.”

Travis had no clue where Afghanistan was, but after sampling a variety of different hashes in Istanbul, he was convinced. He and Bevans dropped the couple off and headed into Iran, where they ran into some trouble: first, their car broke down in Tehran, then Travis got sick with dysentery in Mashhad. After two weeks in the desert, they finally made it to Kandahar—but still had no idea where to find any hash. Luckily, it found them.

“We were standing in line at a fruit stand at the center of the city, and I see this Afghani guy in a turban start walking towards us,” Travis recalls. “He comes right up to me and goes, ‘Do you guys wanna buy some fine Afghan shit?’”

That guy’s name was Nazrullah Tokhi. Nazrullah led them to his little clothing shop where they met his brother Hayatullah, who offered them a sweet deal on some primo hash.

“We’d come there planning to get 10 kilos, but we ended up trading them the car—which was trashed at that point—for 50 kilos of hash,” Ashbrook says. “We still had a lot of money left because everything was so cheap there, so we ended up buying a bunch of strange antique musical instruments and stuffing them with the hash. We packed all of the stuff up with some furs in a big crate and shipped it back to California as unaccompanied baggage.”

After that, they hopped one of the first flights out of Kandahar’s new airport to Frankfurt, then on to LA. The package arrived the day after they got back, where Ricky’s brother Ron was waiting to pick it up. Despite a very close call with customs, the load made it through.

“We thought we’d be coming back with 22 pounds, but we came back with 88 pounds so everybody was really excited,” Ashbrook recalls. “We split it up—each of us and the five investors got 13 pounds, and everyone in the Brotherhood got a pound each.”

Travis had paid approximately $4 per kilo for the best hash in the world, or around $200 for the entire load. Back in Cali, they could sell a single pound for four times what they paid for all 88 pounds! The deal was so lucrative that he started shipping loads of hash back from Kandahar every six months—almost always in vehicles, and almost always from the Tokhi brothers. That went on for years, with loads eventually reaching up to 500 pounds per run.

During these early Kandahar runs in 1968, Travis also brought back a few Afghani chillums (hookahs)—two of which we’ve acquired for our collection [1][2]. They each have a traditional hand-beaded bamboo stem, a ceramic bowl at the top (called a sarhana), and a ceramic base. One of the bowls is wrapped with beaded chainmail to prevent it from exploding from the heat; the other bowl, and both of the bases, are all replicas Travis made out of pottery during the late 1980s.

“Everybody back in Dodge City had one of these pipes in their house,” Travis remembers. “It got to the point where, when you got up in the morning, instead of having your morning coffee you smoked the big pipe. We'd all get together at someone's house in the morning, sit around, and take our chance at the big pipe. Instead of your turn, it was your chance.”

ORANGE SUNSHINE

In spring of 1968, the Brotherhood bought a big property up in the San Jacinto Mountains near Idyllwild known to locals as Fobes Ranch and turned it into their new communal compound and headquarters. Only couples from the inner circle moved there—including Leary, who Travis grew close with and looked up to as a sort of far-out father figure. These were great times for the Brotherhood—hash was flowing in, acid was flowing out, and everybody was living their best life.

That summer, the Newport Pop Festival was held in Laguna Beach featuring some of the biggest names in rock music, and Mystic Arts ran the juice stand at the show (you can guess what was in that juice). There were also visits to the ranch from counterculture celebrities like Ken Kesey, The Moody Blues (who had written a song about Leary), and even the Rolling Stones (who never quite found their way up to the house).

But by far the most consequential happening that summer was the partnership the Brotherhood formed with chemists Nick Sand and Tim Scully, who enlisted them to be the exclusive distributors of their new, ultra-potent LSD which Griggs named Orange Sunshine. Virtually overnight, Orange Sunshine took the counterculture by storm. In little over a month, they had produced around four million hits and were handing them out like candy.

From the surf scene there in Laguna, up to the Grateful Dead scene in the Haight, back East to New York, across the pond to Europe and Asia, and practically everywhere in between—the whole world seemed to be tripping out on what Randall referred to as the “Coca Cola of LSD.” Sadly though, Sunshine didn’t affect everyone in a positive way: it was credited with amplifying the hostility of the Hells Angels at the ill-fated Altamont concert and allegedly inspiring the Manson Family’s horrific murder of Sharon Tate. Nevertheless, for better or worse, Orange Sunshine had become a household name…and the Brotherhood’s trademark.

BOARD BUST

In early 1969, as Travis was about to set off on another run to Kandahar, a friend asked him to bring along a couple of surfboards he’d hollowed out. Brotherhood member Mike Hynson (one of the top surfers in the world) had come up with the idea years earlier—hollowing out long compartments down the middles of surfboards and smuggling Nepalese temple balls from India to Hawaii inside.

Travis agreed, took the two boards with him to Kandahar and filled them with about 10 pounds of fresh hashish each, then shipped them back along with a car. The car (which had about 500 pounds in it) made it back fine—unfortunately, the boards were another matter.

“It was just bad luck,” Travis says. “The boards came into New York during an airline strike and they sat outside in a freight yard for a couple of weeks. The sun heated them up, and the hash started to mold and ferment and rot. The boards swelled up, and the hash got loose. So when the strike was over and they went to load them onto the plane, the hash rattled around and they found it.”

Customs officials helped Travis load the boards onto his car, then secretly followed him with a plane and a caravan of vehicles back to the ranch where they busted him. Luckily, the agents had no idea about the Brotherhood or Leary being up there at that point, so Travis was the only Brother busted. To post his bail, Griggs put up the ranch as collateral.

BUMMER SUMMER

In the summer of 1969, the Brotherhood’s utopian hippie dream began to disintegrate. In May, Leary announced his run for governor of California in front of Mystic Arts World, drawing unwanted attention to the Brotherhood. Within weeks, Mystic Arts World was burned to the ground—allegedly by the John Birch Society, a radical right-wing group whose members were on the Laguna city council.

Next, on July 14, Ricky Bevan’s underage girlfriend Charlene Almeida accidentally drowned in a pond on the ranch while tripping, causing Leary to be arrested on “corruption of a minor” charges. Less than a week later, the ranch was raided—resulting in five more arrests and the seizing of large quantities of pot, hash, and LSD. Then on August 3, tragedy struck again when the Brotherhood’s 26-year-old hippie messiah Johnny Griggs died suddenly of an accidental overdose of synthetic psilocybin.

After Griggs’ death, the ranch was all but abandoned, and the fate of the Brotherhood was suddenly thrown into question. Five months later, Leary was sentenced to ten years for possession of two roaches, and ten more years for another previous pot charge. Not wanting to see their beloved guru rot in prison, the Brotherhood decided to break him out. They spent over six months formulating a plan, then paid radical leftist group the Weathermen (aka Weather Underground) around $20,000 to execute it—allegedly coordinating it all through the Black Panthers and their mutual lawyer Michael Kennedy (who would later represent High Times founder Tom Forcade). Leary escaped on September 13, 1970, and was spirited off to Algeria and into hiding.

With both of the Brotherhood’s spiritual leaders now gone, and prison time for his surfboard bust looming on the horizon, Ashbrook did what any good outlaw would do—he skipped bail and went on the lam.

HENDRIX IN HAWAII

By the fall of 1969, Travis and a few others from the Brotherhood all migrated to Maui, where Hyson and Mundell had already been living since late 1967. Hynson—who had starred in the surfer movie Endless Summer a few years earlier—was collaborating on a new hippie art film that would eventually become the cult classic Rainbow Bridge.

In July 1970, they brought Jimi Hendrix out to the island to perform a free live concert for the film on the slopes of Mt. Haleakala volcano. The Brotherhood had their own tent on the side of the stage during the show, and Travis got to know and get high with the guitar legend during his visit.

“When Jimi came to the island, he hung out with the Brotherhood.” Travis brags. “He hung out with us for a couple of weeks before the concert…he was at our houses every day smoking the pipe.”

According to Ashbrook, Hendrix only played three songs at the show before walking off stage and back to his tent. With a crowd of 10,000 plus high-ass hippies growing restless, Travis tried to persuade Hendrix to get back on stage by offering him some crystal acid. Hendrix was reluctant, so to show Jimi it was “no big deal,” Travis snorted a big line of the crystal. Jimi still wouldn’t take any but did agree to go back out for an extended encore.

“I snorted it and he says, ‘Damn—I'll play for you guys anytime!’ Then he gets up and goes back out on stage.” Unfortunately, Travis never got to see the performance.

“My buddy Johnny Daw says, ‘Do you know how much acid you just took?!?'" Travis remembers. “I said, no—I didn’t even really think about it. He said, ‘You just took well over a hundred hits man! You better go sit down somewhere!’"

"A dose was 200 micrograms—which you can’t even see with the naked eye—and I’d snorted a whole line! Plus I’d already taken a couple of hits and some mescaline earlier that day. I went and laid down, and I can remember him starting to play...and the next thing I know I’m waking up and it’s dark out, and everybody's gone."

Sadly, that would be Jimi’s last recorded American concert—two weeks later, he was dead.

THE "AFFIE"

While on the island, Ashbrook decided to expand his smuggling efforts by bringing in a load of weed from Mexico. He took a crew of four guys, headed down to St. Thomas, and bought a 60-foot schooner appropriately named the Aafje (“Affie”); though its name is actually Dutch, it sounds like it's short for “Afghanistan.” They spent about a month fixing it up, then sailed it over to Guadalajara, loaded it up with 5000 pounds of “really good weed,” and sailed it back to Maui.

“We unloaded it at McKenna beach in broad daylight,” he laughs. “There were like 300 naked hippies living on the beach back then, and they were all just standing there yelling and cheering as we were loading the dingy up and bringing big gunny sacks of weed ashore.” (It was from this load of primo Mexi weed, crossed with seeds from an Afghani load, that the legendary Maui Wowie strain was later born.)

Ashbrook planned to sell that weed, then use the money to buy an even bigger load of Afghani hash—like three or four tons—and sail the boat from Honolulu harbor to Karachi, Pakistan, and back with the load. But before he could set off on the job, he learned from his lawyer that the final appeal on his surfboard conviction had run out and he was forced to flee. On May 1, 1971—the very day he was supposed to turn himself in to go to prison—Travis took off for Honduras. There, he bought a dive resort off the coast and spent over a year laying low…and of course, running hash.

FALL OF THE BROTHERHOOD

It was in 1972 that the Brotherhood’s entheogenic empire finally came crashing down. First, in January, the Feds busted a Brotherhood load of over 1300 pounds of hash in Portland, Oregon—the largest quantity ever seized in the US. A month later, another 729 pounds were seized in Vancouver, Canada. Then on August 5, the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs (precursor to the DEA) executed the largest drug raid in American history against the Brotherhood. Operation BEL, as they called it, was a multi-state, multi-agency operation that executed warrants in Hawaii, Oregon, and California (including the ranch in Idyllwild) that resulted in 57 arrests and the seizure of around $8 million in drugs.

The Hippie Mafia was no more.

“I was in Honduras at the time, and I got warned shortly after that happened that, ‘They know where you’re at and they’re coming to get you.’” Yet again, Travis (and many of his Brotherhood cohorts) went back on the run.

In October of the following year, the US Senate issued a report on Operation BEL entitled Hashish Smuggling and Passport Fraud: "The Brotherhood of Eternal Love," portions of which were later excerpted in the second issue (Fall 1974) of High Times (we have both that issue [3] and an original copy of the Senate report in our collection [4]). According to the report, the operation had resulted in over 100 arrests and 29 indictments, as well as the seizure of 546 acres of property (including four LSD labs, six hash oil labs, and two marijuana canning operations), nearly $2 million in cash, an Orange Sunshine pill press, three tons of solid hashish, over 30 gallons of hashish oil, eight pounds of amphetamine powder, over 13 pounds of cocaine, 104 grams of peyote, 1.5 million doses of LSD, and 3,500 grams of crystal acid, capable of producing another 14 million doses...not to mention an assessment of over $70 million in back taxes.

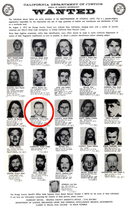

“That was so blown out of proportion,” Ashbrook gripes. “They took every bust over a whole period of time and put it all together to make it look like they did all that right then. Plus the cocaine and the meth and stuff? That wasn’t us. There were so many people that claimed to be in the Brotherhood that weren’t really in the Brotherhood; when the indictment came down, my mother sent me a copy of the wanted poster she took off the post office wall, and I didn’t know over half the people on it.”

You’d think after having his face on a wanted poster Travis would finally hang it up, but no—despite being on the lam for 11 years, he continued to smuggle hash the whole time. In fact, the other items we were able to procure from him for the museum—four cloth hash wrappers—were from loads he ran in 1978 from Baalbek in Lebanon’s Beqaa Valley.

“I was doing a load a year out of there, about five tons at a time,” he recalls. “We had the red, the gold, the blonde—so many different hashes, in different bags, with different colored stamps, that all came from different farms.”

It was on one of these runs that the law finally caught up with Travis. He’d chartered a Lear jet down to Puerto Rico to meet his partner Mario then sail down to St. Martine to pay their Lebanese connection. Unbeknownst to them, the co-pilot was a DEA agent, who secretly searched his hotel room in Puerto Rico and photographed three suitcases filled with $3.7 million in cash. Travis sailed away the next day, but the photos led to an investigation by US Customs, who used his license plate to track him to a post office box he was using back in Cali. From there they followed his wife back to the town of Lone Pine (where they were living at the time), where they observed him using payphones around town.

"They went ahead and tapped every single payphone in the town of Lone Pine!” he laughs. “They spent like a year trying to figure out who the hell I was, then spent another year trying to catch me.”

Asbrook was eventually arrested on October 16, 1980, at Houston International Airport on a flight to the Cayman Islands carrying around $270,000 in cash.

“I got on the plane, they closed the door and pulled away from the gate, and then pulled it right back, came on and arrested me. That way, I had officially left the country so they could charge me with not declaring the money,” he explains. “They busted me, but they never got any hash—it was just all conspiracy and conjecture.”

Ashbrook was charged under the RICO Act “Kingpin Statute” for 36 counts from the Operation BEL indictments—carrying a penalty of life without parole and confiscation of all properties. The first judge threw out the case...but after a successful appeal by the prosecution, he knew he needed to cut a deal. His lawyer negotiated his sentence down to 13 years, plus the five he owed them from the surfboard indictment, for a total of 18 years; he ended up serving 11 of them. (It was during this time in prison that Travis made the bases and bowl for the hookahs).

EPILOGUE

Travis was released in 1991 and returned to his old loves: first making surfboards and running a surf resort in Mexico, then later overseeing a $7 million greenhouse and extraction lab for a legal cannabis company in Nevada.

In November 2011, he and fellow Brotherhood founders Michael and Carol Randall were flown out to Amsterdam to attend the Cannabis Cup and be inducted into High Times’ Counterculture Hall of Fame (which is where I first met him). Having spent their whole lives trying to avoid being identified, they were hesitant to come accept the honor at first…but with some prodding from their old lawyer Michael Kennedy (who was now one of the owners of High Times), they came around.

“We were stoked—we had a great time,” Travis says. “I’d always wanted to go to the Cannabis Cup...I never thought I’d be invited as a VIP! And it was kind of the catalyst to make us decide to go ahead with the movie.”

The movie Ashbrook refers to is Orange Sunshine—the award-winning 2018 documentary film about the Brotherhood, based loosely on the 2010 eponymous book by Nick Schou. “The guy that made it William Kirkley had been bugging us for years and we didn’t want any part of it,” he explains, “but when we were over there we were talking, and with cannabis becoming legal, we felt it was time.”

Travis says that he and the Randalls are now working with Kirkwood to develop a dramatic series about the Brotherhood, which they hope to have in production by next year. He’s also launched his own line of CBD products called—what else—Orange Sunshine CBD. Despite all of the trials and tribulations, Travis has few regrets.

“Well obviously, I’m sorry I got talked into taking those surfboards over,” he chuckles. “But do I regret being in the Brotherhood? Absolutely not. We were truly outlaws, but we had good reasons for doing what we did. We wanted to turn the world on, we were dedicated to our cause, and we knew time would prove us right. Now we're seeing all these states legalizing marijuana and starting to legalize psychedelics. We left our mark, and we were right.”

To dive further down the rabbit hole on Travis & the Brotherhood of Eternal Love, visit the-brotherhood-of-eternal-love.org and belhistory.weebly.com, and listen to Episode 7 of our Cannthropology podcast here or wherever you get your podcasts.

COLLECTION ITEMS:

[1] Brotherhood Afghan chillum pipe with beaded chainmail sarhana bowl and replica base; 1968/1986; Item #S024

[2] Brotherhood Afghan chillum pipe with replica sarhana bowl and replica base; 1968/1986; Item #S024

[3] Second issue of High Times magazine (Fall 1974); 1974; Item #M043

[4] United States Senate Judiciary Committee report - Hash Smuggling and Passport Fraud: "The Brotherhood of Eternal Love"; Oct. 3, 1973; Item #B039

[5],[6],[7],[8] Lebanese hashish cloth bags with colored stamps; 1978; Items #L034, #L035, #L036, #L037