YIPPIE HIGH-YAY!

- Bobby Black

- Apr 14, 2021

- 17 min read

Updated: Apr 14, 2021

The Youth International Party (aka the Yippies) were a radical leftist group founded in the late 1960s that used absurd, satirical stunts to call attention to hippie causes like legalizing marijuana.

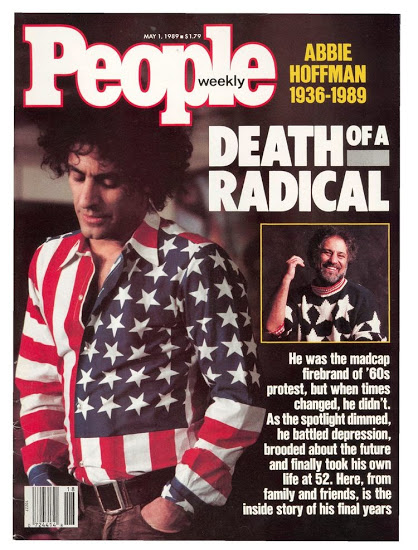

One of the contenders for this year’s Best Picture award at the Oscars is The Trial of the Chicago 7—a drama about a group of activists who allegedly instigated a riot outside the 1968 Democratic National Convention. The most well-known of those activists were Abbie Hoffman (played by Sasha Baron Cohen) and Jerry Rubin (Jeremy Strong)—founders of the anti-authoritarian leftist movement known as the Youth International Party, aka the Yippies.

Occasionally referred to as “Groucho Marxists,” The Yippies were basically radicalized hippies who advocated for the creation of an anarchistic counterculture society divorced from the socio-economic systems of the United States. Inspired in part by the Dutch Provo and San Francisco Digger movements, the Yippies employed absurdist pranks and guerrilla street theater as a means to embarrass the establishment and call attention to causes such as ending the Vietnam War and legalizing marijuana.

![Yippies protest Nixon's inauguration - January 1969. [David Fenton/Getty]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/c4f3e2_9b32698506e3441f9cd783bab59f6086~mv2.jpeg/v1/fill/w_147,h_98,al_c,q_80,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,blur_2,enc_avif,quality_auto/c4f3e2_9b32698506e3441f9cd783bab59f6086~mv2.jpeg)

Among the many counterculture luminaries involved with the Yippies over the years is a man who was personally recruited by Hoffman and ended up succeeding him as the groups’ leader, Dana Beal.

AN ACTIVIST IS BORN

Growing up in Lansing, Michigan, Beal displayed a passion for social justice from an early age. In August 1963, at the age of 16, he hitchhiked to Washington D.C. to attend Dr. Martin Luther King’s historic “I have a dream” speech. Two months later he organized his first demonstration back in Lansing—against the Ku Klux Klan, after their bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham.

Beal smoked his first joint with fellow activist A.J. Weberman at Michigan State University in 1964—beginning a life-long devotion to the herb. Vehemently opposed to the Vietnam War, Beal managed to avoid the draft by getting himself committed to a state mental ward at age 17. Shortly after being declared 4F, however, he went AWOL from the hospital and took off to meet up with Weberman in New York City.

Once there, the pair wasted no time in establishing themselves in the Lower East Side activist scene. On May 30, 1967, the NYPD had beaten and arrested dozens of peaceful hippies sitting on the grass playing music in Tompkins Square Park (an incident that became known as the “Memorial Day Riot”). Two days later, The Grateful Dead showed up to play their first-ever New York show at the Tompkins Square bandshell drawing some 3,000 people to the park. It was against the backdrop of this historic concert that Beal held the first of what would become many weekly “smoke-ins.”

“There had been a sort of mini-riot thing, and we decided that what we wanted to do to mellow things out was hand out free weed,” he says. “And it worked!”

Beal continued hosting pro-pot protests every weekend throughout the Summer of Love—handing out and smoking copious amounts of cannabis at many of the park’s events. Remarkably, he was never arrested—that is, until August 22, when he inadvertently sold nine hits of LSD to a narc. By this time, Beal was already so well-liked in the community that his arrest sparked a series of protest marches: around 200-500 hippies marched from Tompkins Square Park to the local police station, then to the Federal House of Detention, then to the Federal Courthouse, then back to the park where a benefit concert was held (raising $1700), then back to the House of Detention.

The level of support for Beal was so impressive that it attracted the attention of another prominent Provo activist by the name of Abbie Hoffman.

ABBIE & JERRY

A Jewish, socialist, anti-war activist from Massachusetts, Abbie Hoffman had graduated from UC Berkeley then moved to New York in 1963. Originally from Cincinnati, Jerry Rubin was also a Jewish anti-war activist who’d attended Berkley (albeit for one semester). The two met in 1967 when Rubin was incited to New York to help plan an upcoming demonstration at the Pentagon and immediately hit it off.

On August 24, Hoffman and Rubin pulled off one of their first and most celebrated media stunts: the hippie invasion of Wall Street. Accompanied by a group of around 20 fellow activists, Hoffman entered the visitor’s gallery at the New York Stock Exchange and threw out handfuls of $1 bills onto the trading floor—interrupting trading and eliciting both cheers and curses from the brokers below, some of whom scrambled to scoop up the money. The stunt garnered heavy media coverage and prompted the Exchange to install bulletproof glass barriers soon after.

Beal and Hoffman had met earlier that summer at a hippie activist meeting known as the Tribal Council. Seeing that Beal had generated a large following, Hoffman invited him and his crew down to D.C. that fall to participate in a massive demonstration with the promise of four pounds of free weed. On October 21, the Provos joined around 100,000 others in a protest against the Vietnam War at the Lincoln Memorial. Hoffman then siphoned off half the crowd to march across the Potomac to the Pentagon, where they were met by thousands of soldiers from the 82nd Airborne Division.

Hoffman, Ginsberg, and others encircled the Pentagon and led a pseudo-spiritual ritual with the purported goal of exorcising the demons of war and literally "levitating" the building using singing and chanting—fighting the absurdity of war with an equally absurd, more peaceful demonstration. Naturally, their “Levitation of the Pentagon” never actually moved the building—but it did help them define their purpose. After that, all the group needed was a new name.

FROM HIPPIES TO YIPPIES

It wasn’t until three months later, however—while tripping in Abbie's apartment on New Year’s Eve—that their name would come to them, when their friend Paul Krassner (editor of The Realist) shouted out what instantly became the new name for their merry band of miscreants: Yippie!

This exuberant exclamation perfectly captured the essence of their mission and methods. The elaborately acronymized version—the Youth International Party (YIP)—was actually an afterthought, proposed by Abbie’s wife Anita to lend the movement an air of credibility in the press. On January 16, 1968, the Yippies announced their presence to the world by releasing their first manifesto—inviting activists across America to join them for a massive demonstration called the “Festival of Life" in August outside the upcoming Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

Meanwhile, Beal had been arrested again for allegedly selling marijuana—a charge he claims was bogus. Nevertheless, rather than face his day in court, he skipped town, but not before being personally recruited by Hoffman to become one of the first official members of the newly formed Yippies.

THE CHICAGO SEVEN

The 1968 Democratic Convention was held on August 26–29 at the International Amphitheatre in Chicago. Despite being denied permits by the city, approximately 10,000 protestors from various locations and organizations descended on the area in the days leading up to the convention.

The Yippies set up camp in Grant Park and held their own mock counter-convention that featured the nomination of a pig named Pigasus as their candidate. Phil Ochs and the MC5 performed, but the Michigan rockers' set was cut short by one of many skirmishes between police and protestors. To enforce the 11 pm curfew put in place by Mayor Richard Daley, riot police cleared the park using tear gas, mace, and beatings—most of which was aired on live television (prompting the famous chant “the whole world is watching”). By the end of the week, over 1000 protestors had been injured and 600 arrested, including Rubin and Hoffman.

Determined to hold someone other than the cops accountable for the violence, Daley issued a report a couple of weeks later blaming the riots on “outside agitators.” A Grand Jury was convened, and on March 20, 1969, eight activists were indicted for conspiring to cross state lines to incite a riot. Among these “Chicago Eight” as they were called were Rubin and Hoffman. (This moniker was changed to the “Chicago Seven” when a mistrial was declared for Black Panthers leader Bobby Seale).

The trial, which began on September 24 and last over four months, was a national media circus—providing the Yippie leaders the perfect platform on which to perform their political theater. On February 18, 1970, both Rubin and Hoffman were convicted of inciting a riot (and numerous contempt charges) and sentenced to five years in prison (an appeal court ultimately overturned their conviction in November 1972).

BEAL STEPS UP

Beal was a fugitive while all this was happening and was unable to attend the convention. Nevertheless, he remained one of the group’s driving forces—raising money for Hoffman and Rubin’s defense, and later becoming the Yippies’ field marshal after they merged with the White Panthers in Michigan and re-launched in Dec 1969.

“The Yippies had supposedly gone out of existence immediately after Chicago—they got really paranoid and didn’t do anything for a period of time,” Beal explains. “Nobody could figure out what to do, so I got recruited to restart the Yippies and I basically just said ‘Charge!’ and went ahead with a big demonstration.”

That demonstration was the first Yippie smoke-in in Washington D.C. On July 4, 1970, President Nixon held a big rally at the Lincoln Memorial to try to distract from the turmoil going on in the country. Called Honor America Day, it was hosted by pro-establishment stars Bob Hope and Billy Graham and drew around 6,000 people. In one of his first acts as the new de facto leader of the Yippies, Beal organized a counter-rally across the National Mall at the Washington Monument.

Pro-pot, anti-war protestors—some of them naked, waving pot leaves and Vietcong flags and smoking red, white, and blue joints—poured in the reflecting pool, past the police lines and right up to pro-Nixon’s event. They shut it down by chanting over it. After that, both rallies ended—as too many did in those days—in a fog of tear gas and Billy clubs.

Nevertheless, that smoke-in was the first of what would become an annual event. When the Yippies returned in July of ’71 and added an anti-CIA heroin element to the event, their protest was featured on the CBS Evening News. This prompted police to arrest Beal on an outstanding warrant when he arrived in Madison Wisconsin the following week. This, in turn, prompted a crowd of around 2000 activists to stage a smoke-in outside the jail where he was being held. The man who led that protest to free Beal was his friend and fellow Yippie, Tom Forcade.

TOM FORCADE

Arguably the most influential Yippie at the time besides Hoffman and Rubin was Thomas King Forcade. A former Air Guardsman turned drug smuggler from Phoenix, Forcade had connected with the Yippies through his involvement with the Underground Press Syndicate (UPS), which he moved to New York to help run in July 1969. The UPS offices were located in the legendary Fillmore East, where Beal shared office space. But it was actually in March of 1970 at a rally at Yale for Bobby Seale that Beal first met Forcade.

“I met him because he had this special Cadillac tricked out as a stage, so people like David Peel could get up on the stage that was on top of the car and perform,” Beal recalls.

That olive-green Caddy limousine—with the makeshift stage on its roof and air raid speakers strapped to it—was nicknamed “The Star Car” due to the white stars painted on its sides. It was this same military-themed stage-mobile that Forcade later used to terrorize the Medicine Ball Caravan—a concert tour and film designed to emulate the success of Woodstock, which he viewed as corporate exploitation of the counterculture. In August 1970, “Captain Bad Vibes” (Forcade) and his “Caravan of Pirates” (including fellow NYC Yippie David Peel and his band The Lower East Side) followed the Caravan and used counter-concerts, fireworks, and other antics to disrupt the film’s production.

It was for these kinds of in-your-face tactics that Forcade and the Yippies became known —injecting sardonic humor into otherwise serious social/political situations and garnering mass media attention. One such infamous incident occurred at the US Senate on May 13, 1970, where Forcade—dressed a preacher in a clerical collar, coat, and hat—was testifying at the US Commission on Obscenity and Pornography hearing. After spewing a profanity-laden statement denouncing the commission as “unconstitutional, unlawful, prehistoric, obscene, absurd,” he approached the dais with a cardboard box pretending to present evidence and instead shoved a cream pie into the face of one of the committee members.

After that, "pieing" became a signature Yippie stunt; Forcade’s comrade Aron Kay immediately embraced the practice—adopting the name “Pie Man” and continuing to pie many controversial figures for years to come.

DIVISION IN THE RANKS

In December 1971, Forcade and Peel attended the Free John Sinclair Rally in Ann Arbor, where they performed together on stage next to Peel’s buddies John Lennon and Yoko Ono. Forcade had great admiration for Sinclair and had even corresponded with him after he was jailed for his notorious “Ten for Two” arrest in 1970. Unfortunately, neither of them seemed to have as high an opinion of Abbie—especially Forcade, whose differences with Hoffman soon caused a huge schism within the group.

Reportedly, Forcade felt that Hoffman and Rubin were “burned out” after the trial, that they were selling out by endorsing a candidate (George McGovern) for President, and that they were “over the hill” because they were beginning to abandon their past radical tactics in favor of more mainstream activism.

“There was a cultural divide between the Yippies from New York and the kids who were drawn out from the Midwest to protest with them,” Beal once explained in a High Times video interview. “There were like two wings to the Yippies—the entrepreneurial wing, like Tom, who were dabbling in the marijuana business; and the “Steal this Book” wing, which was into all kinds of scams and frauds. And there was always a potential conflict between these two…because what if the people who thought it was cool to rip people off ripped off the people who were dealing pot? That wouldn’t be too cool from the standpoint of, say, a Tom Forcade.”

Their rift split wide open in a dispute over Hoffman’s best-selling paperback Steal This Book. In November 1970, Hoffman had enlisted Forcade’s help with the book. Forcade, who had edited and contributed the book, believed he was owed $3000 for his work; Hoffman, however, claimed Forcade’s work was "inadequate” and only worth $500. To settle the matter, the two agreed to argue their cases before a jury of their counterculture peers in what was dubbed a “Movement Court.” After three weeks of testimony, the court awarded Forcade a “karma alignment” settlement of $1000 plus 10,000 copies of the book at cost. Unfortunately, neither party was happy with the verdict: at the end, Forcade refused to shake Hoffman’s hand, and Hoffman never paid Forcade the agreed amount.

YIPPIE VS. ZIPPIE

The book battle exacerbated the division that had been building within the Yippies between Tom loyalists and Abbie loyalists—so much so that in January 1972, Forcade decided to splinter off and form his own rival faction, the Zippies, or Zeitgeist International Party.

This infuriated Hoffman and Rubin, who officially exiled Forcade from the Yippies and began launching personal attacks against him. Rubin accused Forcade of working with the police and even went as far as distributing a flyer titled “Wanted Tom Forcade” that accused him of dealing hard drugs and using them to manipulate and “string out” activist veterans. Things got ugly fast, descending into threats and incidents of violence. In Pat Thomas’ Jerry Rubin biography Did It!, Weberman claims that Forcade had even put out a “contract” on Rubin over the accusation, which resulted in Rubin being assaulted by one of Forcade’s loyal goons.

The conflict came to a head that summer in Miami Beach, the site of both the Republican and Democratic Conventions that year. Beal, who had been in jail during much of the conflict, was released just five days before the Democratic Convention. When he arrived in Miami, he found himself caught between the two fighting factions; Beal, Weberman, Kay, and Peel all sided with Forcade and became Zippies. They proceeded to lead a 300-person smoke-in outside the convention hall, as well as a takeover of the Democratic campaign headquarters at the Doral Hotel. On August 23, police intercepted Forcade behind the wheel of a van containing gasoline and other chemicals that “could be used as an incendiary device” outside the Republican Convention. The following February, he was arrested and indicted, but was then acquitted weeks later.

HIGHER TIMES

In October 1972, Beal launched the Yipster Times out of the UPS offices—a national underground newspaper devoted to the Yippie culture and causes.

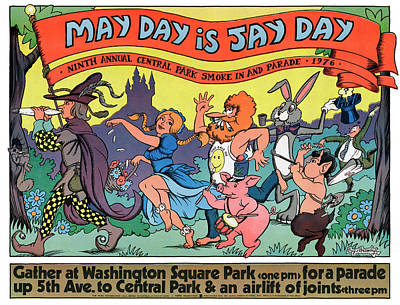

The following May, the New York smoke-in event Beal had helped found years earlier moved from Tompkins to Washington Square Park and ended with a march to U.S. Attorney General John Mitchell’s house—thus making it the first official “May Day” Pot Parade. (We have the original poster from that event in our collection. Titled “Gathering at High Noon for National Marijuana Day,” it features a crowd of various cartoon characters—including the Furry Freak Brothers and the Zig-Zag man, and Uncle Sam holding a machine gun.)

Then in August, Beal took over a three-story building on Bleeker Street in the Bowery. A former smoke-easy, 9 Bleeker would become Beal’s home and Yippie headquarters for the next four decades. He moved in the same month that Hoffman was arrested for intent to distribute three kilos of cocaine—a charge that at the time carried a mandatory life sentence. So in the spring of 1974, Abbie Hoffman skipped bail and disappeared without a trace.

Months later, Rubin issued a public apology to Forcade, Weberman, and Beal: in the Oct. 17, 1974 issue of the Village Voice, he disavowed his previous claims that he believed them to be agents of the police and essentially resigned from the Yippies. With Rubin bowing out and Hoffman missing, Forcade and his faction dropped the Zippie moniker and assumed full control of the Yippies. By that time though, there was a more pressing endeavor that demanded Forcade’s attention: earlier that year, he’d drawn upon his experience and connections in the UPS to launch a new publication devoted entirely to drug culture—High Times.

“That whole time, that was when I was selling weed for Tom,” recalls Beal. “I saw him every night after work…we’d open up the weed emporium. I was putting out my magazine with the money I was making, and he was stealing all of the people I would hire,” Beal chuckles. “We were basically the farm team for High Times.”

TRANSFORMATION & TRAGEDY

Another fateful year for the Yippies was 1978. It was the year the movement began to mature—shifting towards a more disciplined approach to activism and furthering its efforts to heal its lingering divisions. On August 23, they hosted a "Bring Abbie Home” concert rally for Hoffman at Madison Square Garden’s Felt Forum on August 23 (the tenth anniversary of the Chicago Riots) featuring performances by beat poets William Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg, Jefferson Starship, and the cast of Saturday Night Live, among other famous actors and musicians. It was an attempt to lure their fugitive friend out of hiding, funded in large part by money Beal raised by selling Forcade’s weed. Unfortunately, Hoffman never showed up, and the show practically bankrupted the group—but according to Beal, the outpouring of celebrity support helped persuade prosecutors to drastically reduce Hoffman’s sentence when he resurfaced two years later.

Then on November 19, the counterculture community suffered an immeasurable loss, when Tom Forcade—the 33-year old gun-toting, drug smuggling, pie-throwing, manic-depressive genius behind the world’s most notorious magazine—placed the barrel of his pearl-handled pistol to his temple and pulled the trigger.

"Tom, unfortunately, lost his best friend in an airplane accident bringing in a shipment of weed, and became very depressed…and when you’re depressed, don't do coke,” laments Beal. “He shot himself, and the magazine never really had that spark of creativity again. He was a great guy,” Beal remembers fondly. “I really loved him.”

“[Tom] was a great guy,” Beal remembers fondly. “I really loved him.”

MILLION MARIJUANA MARCH

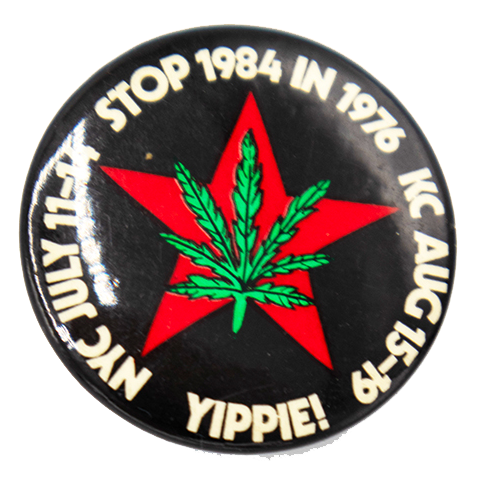

With Beal now squarely at its helm, the Yippie movement soldiered on throughout the 1980s: with chapters in dozens of cities around the country, its newsletter the Yipster Times (later renamed Overthrow) publishing national editions a few times a year, and the two huge, annual smoke-in events he’d helped found: in New York on the first Saturday of May, and in Washington D.C. on Independence Day.

In fact, under Beal’s guidance, the once-modest NYC smoke-in protest evolved into a full-blown parade (up 5th Ave from Washington Square Park to Central Park), and eventually into the worldwide event known as the Million Marijuana March. According to Beal, this global expansion was due ironically to NY Mayor Rudy Giuliani, who, in 1998, attempted to kill the protest by scheduling a corporate-sponsored "Family Day" event in Washington Square the same day, drastically increasing police presence and arrests at the park. The authorities even leaked disinformation to the press claiming that the march had been canceled.

“He shut down our event after 26 years and arrested people for even getting up and announcing that it was canceled," he grumbles. “So we moved from Washington Square down to Battery Park and reversed the course of the parade. And then we called for a worldwide marijuana march to support the proposition that marijuana is a political issue, not just a lifestyle issue. You have a right to medicine, and you have a right to engage in ordinary, harmless behavior that bothers no one.”

Beal connected with some activists over in Britain, and with their help, he re-branded the NYC Pot Parade as the first Global Marijuana March in May 1999. Within a few years, the event had expanded to over 300 cities around the world. We have the poster for the May 5, 2001 march in our collection. Titled “2001 - The Space Odyssey,” it features the names of all of those participating cities, as well as a pair of small mushrooms at the top corners—a hint at why, during this era, the parades were often branded as “Cures Not Wars” events.

“We called the parade here Cures Not Wars because it was also about psychedelic drugs and ibogaine, not just pot,” Beal explains. “Fighting addiction with a War on Drugs is worse than useless—it's misleading. What we need is a cure, not a war.”

Pie Man and Peel remained regular fixtures at the march, as were several High Times staffers. (I myself attended the rally for the first time while still in high school, and then became a regular during my time at High Times in the 1990s-2000s.)

DENOUEMENT

Sadly, things did not end well for most of the Yippies’ most famous figureheads:

Forcade's fate we've already covered. Thankfully, despite his untimely death, his brainchild High Times survived and has continued to inform and shape the counterculture for decades.

After nearly six years on the lam, Abbie Hoffman resurfaced in September 1980 and sat for an interview with Barbara Walters, where he revealed that he’d underwent plastic surgery to change his appearance and was living under an assumed identity in upstate New York. After turning himself in and agreeing to participate in an anti-heroin promotional campaign, he served just eight months in rehab. But sadly, like Forcade, he was also diagnosed as bipolar and committed suicide by overdose in 1989. (The same year that Yippie newspaper Overthrow ceased its publication.)

Jerry Rubin went from Yippie to yuppie—selling out by becoming a broker and going to work at the very stock exchange he once disrupted in protest. He was hit by a car and died on the streets of Los Angeles in 1994 at the age of 56.

David Peel continued his mission of music and activism in the Lower East Side until the ripe old age of 73 when he died from a heart attack in 2017.

Thankfully, Weberman, Kay, and Beal are all still alive and well—kicking around the streets of New York thumbing their noses at the man and fighting for the social causes they’ve devoted their lives to (in Beal’s case, being the legalization of both cannabis and ibogaine—the all-natural anti-addiction drug he’s championed for decades).

Beal continued to plan and run the marches from 9 Bleeker until 2011 when he was arrested for marijuana trafficking in Wisconsin. (The European Coalition for Just and Effective Drug Policy took over the global march in 2017, though Beal remains the event’s figurehead). Beal purchased the building in 2004 and soon after opened up the first floor to the public as the Yippie Café & Museum. The Museum—which featured such curiosities as a portion of Rubin’s remains and Timothy Leary’s ashes, as well as flags and various other memorabilia—was eventually chartered by the New York State Board of Regents. Sadly though, while Beal was incarcerated in summer 2013, the Yippie Museum was forced to close its doors, and in 2014 the building was foreclosed on and sold. According to Beal, much of the Yippies’ archives and memorabilia tragically ended up in dumpsters.

MODERN PROBLEMS

Over the past decade or so, Beal has been arrested for trafficking marijuana four times—all but one of which were essentially dismissed. In September 2011, while in custody in Wisconsin awaiting transfer to state prison, he suffered a heart attack and was dead for three and a half minutes before being revived. He spent a week in an induced coma before undergoing double bypass surgery, then serving a five-year sentence. Since his release in February 2017, Beal has remained effectively without a home or source of income. Nevertheless, he remains hopeful for the future: he’s starting his own ibogaine company and looking forward to finally seeing the fulfillment of his life’s work—the end of prohibition—which he believes is imminent.

"The War on Drugs is no longer at the top of the list of things to deal with in the country. They just don't have the bandwidth to have a war on weed anymore," he observes. “It's impossible to go to jail for pot anymore. They’re like phantom busts—they just take the weed and basically let you go. That's how I know legalization is actually coming.”

For more about Dana Beal and the Yippies listen to Episode 11 of our Cannthropology podcast. For current info about the Global Marijuana March visit cannabisparade.org or facebook.com/GlobalMarihuanaMarch.