THE GURU OF GANJA

- Bobby Black

- Nov 18, 2022

- 14 min read

Over the past half-century, Ed Rosenthal has authored or co-authored nearly 20 books on cannabis which have collectively sold over two million copies. The eccentric cultivator, activist, and educator is also credited with discovering Durban Poison and Afghan #1, and cofounding both High Times magazine and Amsterdam’s famous Hash, Marihuana and Hemp Museum. It’s no wonder he’s come to be known as “the guru of ganja.”

PLANTING THE SEEDS

Edward Rosenthal was born on December 2, 1944, in the Bronx, NY. Growing up in what he describes as “a typical dysfunctional family of the ’50s era,” his childhood and adolescence were "very unhappy"—causing bouts of depression serious enough for him to seek therapy. As an escape, he developed an interest in horticulture at an early age, even taking classes at the New York Botanical Garden—a hobby that would later become his life’s work.

"If you were interested in plants and grew up during hippie times, you sort of just gravitated to learning more about marijuana," he told the SF Gate in 2002.

Though he doesn't specifically recall the first time he smoked marijuana, he knows he was around 21.

“I first started in 1966,” he said in a 1984 interview with High Times. “I had tried it a couple of times in 1965, but I never got high. Then in 1966, I bought a lid, and I smoked it with my college roommate… I remember thinking, ‘This is the greatest thing that’s ever happened in my life.’”

Naturally, his passion for plants kicked in: within a few years, he bought some fluorescent lights, planted some seeds he found in the Mexican weed he’d procured, and started growing weed for himself.

“I was living in a very large apartment with several roommates, and we had a spare room. So rather than get another roommate, I decided to have a bunch of “girls” live there,” he teases.

THE YIPPIES

In 1967, Rosenthal dropped out of college and went to work for the brokerage firm L.F. Rothschild and Company (the same company that years later produced the "Wolf of Wall Street" Jordan Belfort). Living in the East Village, he was working stock compliance during the day, but transformed into a hippie by night. Eventually, he grew restless and left the firm to fully immerse himself in the city’s thriving counterculture and pursue his real interests—namely, activism and cannabis.

“In 1967, I went to a "Be-In" in Central Park, and Abbie Hoffman was onstage. He jumped down from the stage, started handing out acid, and said to me—really impersonally, as he had been for thousands of others—‘Wanna trip?’ And I said, ‘Yes.’ He put a tab on my tongue, and I swallowed it and went through a really powerful…horrible experience,” Rosenthal recounted to High Times. “All the shit and all the negativity that had accumulated all my life started coming out. I didn’t say, ‘This is a bad trip, this is terrible, this is terrible.’ I realized what was going on. It wasn't the acid or anything—it was what was in my own head that was coming out. Shortly after that, I never suffered from serious dysfunctional depression again. I really learned to control my state of consciousness."

Around the same time, he fatefully encountered another soon-to-be activist icon.

“One day, I walked out of my apartment on East 10th Street between First Avenue and Avenue A, and I noticed that there was a march going on. I had nothing to do that day, so I said, 'Well, what's it about?’ And they said, ‘this guy has been arrested and has been taken to the federal building on the west side.’ ‘Okay, what was he arrested for? Oh, for selling acid? Well, that's a good thing to march for.’ So the fellow who had been arrested was a person by the name of Dana Beal, and Dana was in a political organization that would eventually become part of the Yippies.”

After the march, Beal was released, befriended Rosenthal, and recruited him into the Youth International Party (Yippies).

“I was a very active member,” Rosenthal assures me. “I was in the inner circle, but I wasn't at the club all the time—I also had a life.”

TOM FORCADE

It was through his association with the Yippies that Rosenthal eventually met pot smuggler/dealer—and Underground Press Syndicate director—Tom Forcade in 1971, with whom he quickly sparked a friendship.

“Tom was a very fucked up person,” Ed opines. “He had a very weird diet—the only thing he ate was hamburgers. And everybody else was into rock music of some sort, but his favorite band was a discordant German band called Tangerine Dream. He was very, very weird.”

One day, during a smoke session in the Village, the friends came up with a brilliant idea.

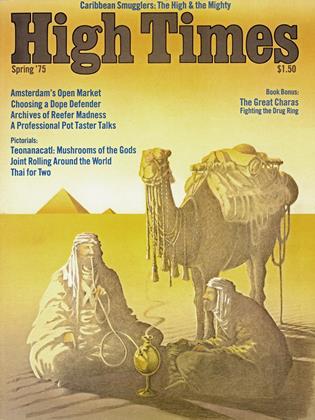

“Tom, a fellow by the name of Ron Lichty and myself, we were all living in a collective down on 11th Street and were all part of the Underground Press Syndicate, and we had a little bit of money in that organization. And then, I had visited this guy, Peter Knocke, at the University of Florida. He had done a study on the increase in rolling paper sales, which was an indirect way of measuring the increase in marijuana use. So we did some figuring and using the most conservative estimates, we got these figures that were way, way beyond anything that the official record said. And from that, we decided it was a large enough audience to justify starting a magazine. And that magazine became High Times.”

The trio sat down and mapped out 100 different article ideas they planned to publish over the first few years. Unfortunately though, despite being “at the heart and soul of that magazine at its inception,” Rosenthal was never credited as cofounder and never got to write any of those articles, because shortly after conceiving the magazine, Forcade threatened Rosenthal and threw him out, all on the advice of one questionable acquaintance.

“There was a guy, he was a good friend of Tom's, that was working undercover for the government,” Ed alleges. “I don't know what government agency he worked for, and I'm not going to name him because I don't have proof of it, but he tried to destroy the magazine, and Tom never knew it until after this guy disappeared from his life. He had not done the damage he'd hoped to do, but he’s the one who split us apart.”

THE GROWERS GUIDE

Because of his falling out with Forcade, Rosenthal didn’t end up writing for High Times until after Tom’s death in 1978. But thankfully, he didn’t need HT to establish himself as an expert in cannabis cultivation. In 1971, after a brief stint as a dealer, Rosenthal began building, selling, and installing small greenhouses for growing weed. As part of his marketing plan, Rosenthal went to the offices of Rolling Stone, offering to write an article about growing pot in an attempt to get his product included in one of their "New York Flyer" supplements.

As it happens, another cannabis cultivator going by the pen name Mel Frank had beaten him to the punch—writing an article for the Flyer about growing marijuana under fluorescent lights. His two-part feature, "A Grow-Your-Own Guide for New Yorkers," was the first cannabis cultivation article ever published in a major magazine.

After reading the article, Rosenthal accepted an offer from the editors to arrange a meeting with Frank. The two hit it off, and within five minutes of meeting him, Rosenthal had suggested they collaborate on a book. Though reluctant at first, Rosenthal’s persistence eventually persuaded Frank. Building upon Frank’s article and Ed’s experience, they gathered as much information as they could find at the time.

As part of their research, they traveled down to the University of Mississippi to meet with Dr. Carlton E. Turner, a research associate at the Marijuana Research Project—the only legally sanctioned, federally funded cannabis farm in America. Under contract with National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), the MRP was used to grow weed for governmental research and to supply medical marijuana to a select few test patients (such as Elvy Musikka and Irvin Rosenfeld) as part of their Compassionate Investigational New Drug program.

Turner provided them access to a bibliography of the various scientific papers on pot that had been published over the past several years. Using the wealth of information gleaned from those papers and their own knowledge of horticulture, the duo produced the 94-page that would become the first comprehensive textbook on cannabis cultivation: The Marijuana Growers’ Guide: Indoor/Outdoor Highest Quality.

In August 1973, after the manuscript was done, Ed moved out to San Francisco, where he began shopping around for a publisher. In 1974, San Francisco’s Level Press agreed to publish the first edition of their groundbreaking grow manual. (In an ironic twist, when HT first began publishing that same year, it was Frank who penned their first grow advice column rather than Rosenthal.)

A few years later, another publisher—And/Or Press—published a new, deluxe edition of the book—a version that, in August 1978, was actually reviewed in The New York Times (the first and only grow book to receive that honor). Thanks in part to that review, their bud bible ended up selling over a million copies—informing and inspiring an entire generation of ganja growers and establishing Mel Frank and Ed Rosenthal as America’s leading authorities on cannabis cultivation.

WEST COAST ACTIVISM

Riding high on their newfound success, in 1977, Ed and Mel bought a house together in Oakland. Of course, that wasn’t the first time Rosenthal had spent time in California: He’d first visited the Golden State in October 1971 at the urging of Dr. Michael Aldrich, cofounder of the cannabis activist group Amorphia. Rosenthal had met Dr. Aldrich (and many other prominent activists) at the very first conference of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws held in the basement of a church in Washington DC, where NORML founder/director Keith Stroup had invited him to speak about cultivation.

“I had been in Rolling Stone, so I went down there,” he told HT. “I met Mike Aldrich at the conference, and he said, ‘Come out to California—we’re having a ’72 initiative.’ So I decided to go to California … to work on the initiative.”

That initiative was Proposition 19—the first attempt to legalize marijuana by ballot measure in the history of the United States. Put together by the California Marijuana Initiative (CMI)—which included Stroup, Dr. Aldrich, his wife Michelle, and others—Prop 19 would have legalized the personal use, possession, and manufacture of marijuana by adults in the state of California.

After the measure was roundly defeated at the ballot box, Rosenthal returned to New York to complete the book with Mel.

MARIJUANA MUSEUM

In 1985, Rosenthal flew out to Amsterdam, which was the center of the cannabis cultivation world at the time. There, he met with many of the top breeders, growers, and coffeeshop owners, including Mellow Yellow founder Wernard Bruining and his “Green Team” grower Old Ed Holloway, Skunkman Sam, and Karel Schelfhout of the Super Sativa Seed Club, (SSSC), as well as the infamous Nevil Schoenmakers of the Holland Seed Bank, whom Ed had mixed feelings towards.

“He was a great breeder, but he left something to be desired as a human being,” he says of Schoenmakers. “I think the Australian sun fried his brain in some way.”

While in Amsterdam, Rosenthal was contracted by two coffeeshop-owning Dutch brothers to curate the first international cannabis museum.

“They’d put together this whole museum—it had all the counters, all the exhibit spaces… it was only missing one thing: the exhibits. It had to be filled, and they needed somebody who could do it in three weeks. So I put together a team, worked 16 hours a day, and we got it done.”

In 1987, Sensi Seeds owner Ben Dronkers purchased that project and rebranded it as the Sensi Hash Marihuana & Hemp Museum. A few years later, Dronkers also bought the Seed Bank of Holland from Schoenmakers when he was forced to flee the country during Operation Green Merchant. Interestingly, it was Rosenthal who introduced Nevil to Dronkers, whom he’d become friends with. (Years later, Dronkers would even name a strain after him called “Ed Rosenthal Super Bud.”)

HIGH TIMES

It was also in 1987 that High Times held its first-ever Cannabis Cup in Amsterdam, which Rosenthal helped organize. It was a small private event featuring only a handful of seed companies and a select few expert judges, of which Rosenthal was included.

By then, he'd long since been welcomed back into the fold at HT. After Tom Forcade’s suicide in 1978, Rosenthal soon became a regular contributor to the magazine—most notably, his monthly Ann Landers-style grow advice column “Ask Ed.”

Premiering in 1983, Ask Ed was published every month for 17 years, becoming the longest-running column in the magazine’s history. That is, until it was discontinued in 2000 after a dispute between Rosenthal and the magazine’s owners regarding the publication’s rightful ownership.

As previously discussed in our September 2021 column “Radical Law,” Forcade had set up a trust to fund the magazine after his death, with the stipulation that in the year 2000, the trust would be dissolved and ownership of the magazine would reportedly be passed to "loyal employees" who'd been with the company for ten years or more (Rosenthal claims it was five years, but every other account I’ve heard said it was 10). Rosenthal, along with former editor Andy Kowl, believed they qualified under the trust’s provisions to receive shares in the company. The trustees, however, disagreed. Forcade’s cousin John Goodson—the attorney who originally drafted the trust—refused to reveal the trust's value and claimed that Rosenthal was merely a freelancer who wrote for the magazine in exchange for ad space to sell his books.

Moreover, he claimed that Forcade's will had intended significant amounts of money and other assets to be donated to NORML over the previous three decades. He alleged that millions of dollars of revenue were instead pocketed by the company’s trustees—namely, Forcade’s family, his former lawyer Michael Kennedy and his wife Eleanora (who ended up with the majority of the shares).

As a result, Rosenthal filed a lawsuit against HT's parent company Trans High Corp. seeking to force them to disclose the trust’s value and award him the shares he felt he was rightfully owed—a lawsuit that not only caused a rift with HT but also with NORML, with whom Rosenthal’s ties remain “tenuous” to this day.

“Until the year 2000, all the profits were supposed to go to NORML. They never went to NORML— NORML never got any profits. I was on the board of NORML, and when I brought this up, Keith said, ‘Oh, I didn't know about that.’ And I said, ‘You didn't know about that? Is this your signature?’ ‘Yeah.’ And then Don Wirtshafter had found the whole thing for the trust that Keith had signed onto. And so it turned out Keith had been lying to the board. And to this day, I think there was some corruption or rot there, and when Wirtshafter brought it up to the board, they removed him from the board.”

Rosenthal ultimately lost the suit—which he attributes, at least in part, to foul play.

"They paid off one of my lawyers, and he just stopped working for me," he claims. "After that, I represented myself, and the judge said, 'you should have been representing yourself earlier because you probably would've won. You gave the most cogent stuff, but it's too late.' "

“They refused to give me any shares because they knew that if I got in there, their corruption and rot would be gone,” he continues. “If I had been in there, it would've been a very different magazine. It would’ve had more of a political slant than it does today. So it was unfortunate, but life goes on.”

UNITED STATES v. ROSENTHAL

Speaking of misfortune, Ed’s lawsuit against HT wasn’t the only time he’d find himself in court during this period of his life; like many other cannabis cultivators and activists, Rosenthal eventually found himself in the crosshairs of the DEA when, on February 12, 2002, federal agents raided his home and nursery in Oakland.

"It was six in the morning, and there was banging at the door. Since I sleep naked, I went down naked to see what was happening… so they knew I was unarmed,” he jokes.

Rosenthal was charged with the cultivation of over 100 plants, but the irony of the arrest was that the city legally permitted his garden; in 1999, he’d been appointed an “Officer of the City of Oakland.” In other words, he was deputized under Prop 215 to grow those plants, cuttings of which were set to be distributed to various medical marijuana clubs around the Bay Area. Word of his arrest spread quickly, and the community rallied around him—even high-ranking city officials.

“Within a short time, the public knew what was going on. The head of the DEA, Asa Hutchinson, was in San Francisco to announce [the bust]. He was on the radio, and he was getting very derisive remarks. Later that day, he had a speaking engagement at the Commonwealth Club and was roundly booed. The district attorney of San Francisco, Terence Hallinan, was even outside with a bullhorn making nasty remarks about the fellow.”

To help cover Rosenthal’s substantial legal bills, activist Virginia Resner founded Green Aid: The Medical Marijuana Legal Defense and Education Fund—a charitable organization whose mission is to provide legal and financial assistance to medical marijuana patients, providers, and activists. In March 2003, the organization held a fundraiser dinner at Rosenthal's home, attended and donated to by some of his high-profile friends, including Tommy Chong, George Zimmer, Ben Dronkers, and others.

Although Rosenthal's garden was a non-profit medical grow that had the blessing of the city and was legal under Prop 215, his lawyers were prohibited from presenting any of that information as part of their defense because the case was federal, and therefore state law didn't apply.

“The jury was never allowed to find out what was going on. They were never allowed to know that it was medical, that it was approved by the city, and that I was an officer of the city allowed to do this, even though the city attorney had testified on my behalf in hearings before the trial.”

Recognizing that the trial was a farce, Ed drew on the old Yippie playbook once employed in the Chicago 7 trial—drawing attention to the absurdity of the case with equally absurd theatrics—wearing a flamboyant “Wizard of Weed” costume to court. Tactics like these helped draw national media attention, as well as crowds of protestors outside the courthouse, and ended up moving the needle on the public’s opinion on medical marijuana. Nevertheless, without the ability to mount a viable medical defense, he was convicted in 2003. But after the trial, when the jurors learned about the mitigating circumstances they’d been prevented from hearing about, most of them recanted their verdict and begged Ed for his forgiveness.

“At my sentencing hearing, 10 of the jurors show up, and they give a news conference saying that they were terribly wrong and were duped by the judge. That was the first time in American history that ever happened, to my knowledge,” Rosenthal says. “The jurors felt so guilty that I had to console them! I had to go hug them because they were all crying. They felt terrible.”

Capitulating to intense social pressures from the public, jurors, and reportedly even his own wife, US District Court Judge Charles Breyer sentenced him to just one day in jail, time served.

“The judge and his wife Cindy were socialites, and they weren't getting invited to parties anymore,” Rosenthal claims. “Believe me, it wasn’t for me that he did it—it was to save their own social life.”

Three years later, the 9th Circuit Appeals Court overturned his conviction (on a technicality) due to jury misconduct. Apparently, one of the jurors had asked a friend who is an attorney whether she was required to vote according to the law or if she was allowed to vote her conscience. Her friend told her she had to follow the judge’s instructions or she could end up in “trouble.”

With the first trial essentially negated, the US Attorney's office decided to re-indict him months later—instigating a second trial in May 2007, presided over by the same judge. Once again, Breyer prohibited the defense from presenting evidence that the city and state sanctioned Rosenthal's work, and once again, he was convicted—on three of the five charges against him.

“I was found guilty again. But here's the thing: I had already done my time, so they couldn’t sentence me to anything. So after I was found guilty, I just walked out. They’d given me a day, and I had done 36 hours, so they actually owe me 12 hours,” he jokes.

Though he narrowly escaped the long arm of the law, he remains committed to helping those who were not so lucky, most visibly in his capacity as Green Aid’s executive director.

GIVING BACK

Now, at age 77, Rosenthal is at the peak of his prestige. He’s won lifetime achievement awards from numerous cannabis cultural institutions, including the International Cannabis Business Conference (ICBC), the American Medical Marijuana Association (AMMA), NORML, and the Emerald Cup, as well as a 420 Icon award from World of Cannabis / Cannabis Business Awards. He continues to make appearances and speak at cannabis events around the world (occasionally wearing a flamboyant costume such as a “weed wizard” or a superhero called Can Man) and run the publishing company he founded nearly 48 years ago, in 1974, Quick Trading, with his wife of 33 years, Jane.

The numerous books he's written (or co-written) include the Big Book of Buds, Beyond Buds, Marijuana Harvest, Marijuana Garden Saver, Why Marijuana Should be Legal, and the best-selling Marijuana Grower’s Handbook (the cultivation textbook used at Oaksterdam University).

His most recent book, The Cannabis Grower’s Handbook: The Complete Guide to Marijuana and Hemp Cultivation, is a modern reinvention of that classic.

His latest project is the Million Marijuana Seed Giveaway—committing to give away one million seeds of different cultivars he and his friends have bred in an effort to encourage his fans to become pheno hunters. Some of those free seeds are included in the “Prisoners of Weed” book packs for sale on his website, with ten percent of the proceeds going to the Last Prisoner Project to support pot POWs. So far, his POW packs have raised over $6000 for the organization.

“This is a real win-win-win,” Rosenthal recently told High Times. “I didn’t have to do time after I was raided… but there are still people out there doing time for a plant many are profiting on now, and that’s wrong. We need to change that yesterday.”

For more on Ed and his books, visit his website at www.edrosenthal.com.

Podcast episode coming soon!

Comments