AMSTERDAM'S CANNABIS REVOLUTION - PART 1: POT PROVOCATEURS

- Bobby Black

- May 23, 2021

- 11 min read

Updated: May 24, 2021

How a handful of activists and entrepreneurs transformed the Venice of the North into the cannabis capital of the world.

If there’s one city in all the world most associated with marijuana, it is undoubtedly Amsterdam. The very mention of the name immediately conjures to mind images of bustling bike lanes, shimmering canals, rows of glowing red lights, and yes, smoke-filled coffeeshops. For decades now, the city has been known for its liberal attitudes toward cannabis (and sex)…but it was not always this way. Like most other sociopolitical sea changes in the past century, the Dutch policy of cannabis tolerance—and the coffeeshop industry that sprang up around it—traces back to a handful of counterculture activists and visionaries in the late 1960s and early 70s who pushed back against the powers-that-be and paved the way for the thriving cannabis culture that followed. In the Netherlands, those activists were the Provos.

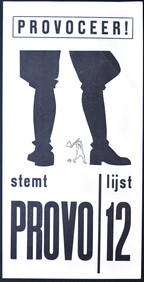

THE PROVOS

Like America’s Diggers and Yippies (who they helped inspire), the Provos (short for provoceren, the Dutch word meaning “to provoke”) were a radical activist group that combined non-violent political protest with absurd humor and guerilla street theater as a means to promote their liberal agenda and goad authorities into extreme reactions that would end up exposing their hypocrisy and embarrassing them in the media. The most prominent figure in the Provo movement was an anarchist performance artist by the name of Robert Jasper Grootveld.

Born in Amsterdam on July 19, 1932, “Jasper” (as he was known to his friends) had an anarchist for a father, who instilled in him a strong anti-authoritarian streak. A beatnik and a loner, he dropped out of school and worked a series of odd jobs before becoming a full-time activist. Grootveld’s life became a rebellion against the rigid, puritanical, and commercialized mindset of Dutch society of the time; starting in the early 1960s, he began staging a series of demonstrations known as “happenings” designed to mess with the man and deprogram the masses, whom he believed had been reduced to brainwashed consumers.

THE MARIHUETTE GAME

In 1962, Grootveld and his comrades launched a guerilla pro-pot disinformation campaign called the "Marihuettegame" (marijuana game), the rules of which they published in a manifesto entitled “Marihu #2.” The premise of the game was to score “points” by tricking police into trying to bust you. Participants would narc on themselves, but when police acted on the tip, instead of marijuana they’d only find what Grootveld called “marihu”—legal substances that bore a resemblance to marijuana, such as herbs, straw, wood shavings, etc. For example: If you got the cops to search your house, you’d earn 50 points; if you actually got arrested for the marihu, you got 100 points; a voluntary visit to the police station was worth 150 points, and so on. These points could then be redeemed for actual weed at the Afrikaanse Druk Stoor—an underground counterculture shop they operated out of his friend Fred Wessels’ house in the Jordaan.

The purpose of the Marihuettegame was to demonstrate the authorities’ ignorance about cannabis, get them to waste their time and resources on false alarms, and make them grow so weary of following up on bogus leads that they’d give up on chasing after pot smokers altogether. Apparently, their stratagem worked—as evidenced by the following anecdote by Grootveld published in the book Really Free Culture: Anarchist Communities, Radical Movements, and Public Practices:

"One day a whole group of us went by bus to Belgium. Of course, I had informed my friend Houweling [a police officer] that some elements might take some pot along. At the border, the cops and customs were waiting for us. Followed by the press, we were taken away for a thorough search. The poor cops…all they could find was dog food and some legal herbs. 'Marijuana is dog food,' joked the papers the next day. After that, the cops decided to refrain from hassling us in the future, afraid of more blunders."

THE ANTI-SMOKE MAGICIAN

As vehement a proponent as Grootveld was of cannabis, he was even more zealous in his opposition to cigarettes. A begrudged smoker who blamed the tobacco and advertising companies for his nicotine addiction, he spent much of his early activist years waging a personal war against these industries—scrawling the word “kanker” (cancer) in black onto every cigarette pack and billboard he could find and scaring customers out of tobacco shops.

Then in June 1964, he read in a local newspaper about how a statue of a little boy in Spui Square called Het Lieverdje (“The Little Darling,” which in Dutch slang meant “little rascal”) had been donated to the city by the Turmac tobacco company and was incensed. The journalist wrote something to the effect of: "We do not know what will become of this little boy…we don’t know the future.’ Upon reading that, he reportedly responded: ‘I know what this little boy will become—he will become an addict to tobacco!”

Grootveld began staging anti-tobacco happenings at the statue every Saturday at midnight. Dressed up as an African witch doctor/shaman (blackface and all...and no, it wasn't meant to be racist), he’d dance around in a "manic euphoria" singing the "Ugge Ugge" song (“Cough Cough,” their anti-smoking jingle), and encouraging attendees to sacrifice their cigarettes to the bonfire at the base of the statue—a bizarre ritual that earned Grootveld the nickname the “Anti-Smoke Magician.” These happenings continued for close to a year—drawing hundreds of people, tons of media attention, and quite a few beatings from police. It was at these demonstrations that Grootveld first met fellow anarchists Roel Van Duyn and Rob Stolk, with whom he co-founded the Provos on May 25, 1965.

In the years that followed, the Provos published several magazines, manifestos, and leaflets, held many other happenings (including one called Stoned in the Streets) and launched a number of radical progressive social campaigns known as the “White Plans,” the most famous of which was the anti-automobile White Bicycle Plan. Against the city's wishes, the Provos painted 50 bikes white and dispersed them throughout the city for free public use (the world's first bike-sharing program), for which they were beaten and arrested by police.

They also notoriously disrupted the royal wedding procession of Queen Beatrix with smoke bombs in March 1966.

Naturally, actions like these made national headlines and eventually led to huge societal upheavals, including a riot in Dam Square, the firing of Amsterdam’s police chief, the resignation of the mayor, a congressional investigation, and a near cultural civil war within the country. Before long though, more and more of the Provos’ ideas were embraced by the mainstream population and the group effectively rendered itself obsolete. On May 13, 1967, Provo was officially disbanded. Some members assimilated into the political establishment, while others fell in with the growing hippie movement. Such was the case with Grootveld; he became a full-time cannabis activist, and with the aid of a fellow Provo named Kees Hoekert, ushered in a green new era for Dutch society.

THE GRANDFATHER OF DUTCH WEED

Other than Grootveld, no figure is more central to Amsterdam’s cannabis history than Kornelis “Kees” Hoekert. Born in 1929, Hoekert grew up in a strict Protestant family in the Veluwe region of the Netherlands (a woodland area about an hour east of Amsterdam). From an early age, Hoekert felt a burning wanderlust which he termed “horizon fever.” In 1951, while on holiday in Tangier, Morocco, he smoked kif for the first time and it was a revelation: not only did he enjoy it immensely, he also realized that contrary to what he’d been taught, cannabis was not harmful or addictive.

Hoekert spent the rest of the decade working first as a teacher, then for three years as a steward on various cruise ships before ending up in Paris, where fell in love with a French girl named Marie-José. In 1960, he brought her back to Amsterdam, where they got married, had two children, and lived on a houseboat he'd purchased on Wittenburgergracht (not far from Centraal Station) called De Witte Raaf (The White Raven). Three years later, his wife took the kids and left him. Newly unencumbered by familial obligations and seeking a new direction for his life, Hoekert decided to pursue his passion for cannabis full-time.

Like Grootveld, Hoekert was a disgruntled tobacco addict who preferred smoking weed and hashish instead. But he didn’t like the imported black-market hash that was available due to its questionable quality (camel and elephant dung were allegedly often passed off as hash), and unfortunately, there wasn't really much cannabis around.

“Cannabis didn’t exist at the time—it was all hashish,” Hoekert told me during an interview for High Times in 2009. “The hashish back then came from Morocco or Afghanistan. Marijuana was not brought into Holland because it was too bulky—difficult to smuggle. So the only thing you could get in those days was either hashish or what they called ‘lowland weed,’ which is no good to smoke.”

Hoekert’s desire for decent weed led to another of his marijuana misconceptions being disproved: like everyone else in Holland at the time, he believed that cannabis was an exotic crop that had to be imported because it could only be grown in specific regions and climates. Nevertheless, he decided to try growing out some hemp seeds on his boat, and much to his surprise the plants thrived. The results of his first few harvest didn't produce any high...that is, until after he received some seeds in the mail from an acquaintance in America. Thus, it was Hoekert who first realized that good cannabis could actually be grown successfully right there in Holland.

“I thought, ‘I have discovered something remarkable’—I realized that you can grow marijuana everywhere,” said Hoekert. “I wanted to publicize this so that everybody knows it. So what do I do?”

Enter Jasper Grootveld. One morning, he read a newspaper article about a man who was growing weed on his houseboat and decided to go meet him. Having already connected with the Provos earlier (the smoke bombs later thrown at the Queen’s carriage were actually made on the Raven), Hoekert immediately bonded with Grootveld and the two kindred spirits decided to join forces to spread the word about cannabis. Thus, a partnership—and a revolution—was born.

“It was me and Jasper—two men who understood each other,” Hoekert remembered fondly. “We had smoked marijuana long before the entrance of hashish. We thought, ‘Why smoke hashish when we can grow the best weed here in Amsterdam?’ We talked about it and said to ourselves, ‘We have to bring back cannabis and all the knowledge we have about it to Amsterdam and warn about hashish. How do we spread the word?’”

The duo formulated a plan for a new Provo-style campaign to normalize and legalize weed. Step one was to begin planting seeds in random places all over the city—in parks, the forests, by the airport…anywhere a plant might take root. And in a new take on Grootveld’s old Marihuettegame, Hoekert embarrassed the police by tricking them into planting cannabis right in front of their station.

“I go to the police station and say, ‘I’m a plant lover—may I bring some presents for your garden?’ And they said, ‘Oh, lovely plant,’ and they planted it in front of the station. They didn’t even know if ‘marijuana’ meant a little town in Spain or a plant!” Hoekert laughed. “Then I go to the press and tell them I have a secret: At police headquarters, they are growing marijuana in flower pots!”

In addition to planting them, Hoekert also began handing out seed packets to random passersby and motorists.

“There’s a big tunnel where people come to Amsterdam from Germany,” he recalled. “I put my pockets full of seeds and posted myself at the end of the tunnel. The cars had to stop there for the traffic light, so when they stopped, I would say, ‘Welcome to Amsterdam! Here are some flowers!’ I did that for weeks. They were always curious: ‘What kind of seeds are these?’ ‘Tulips!’ I would say.”

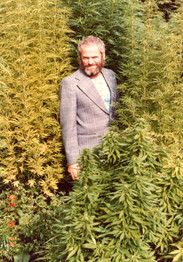

LOWLANDS WEED COMPANY

After playing Johnny Appleseed all across Amsterdam, Kees and Jasper were ready to take their mission to the next level: in 1969, they bought a kilo of hemp seeds from a nearby pet store (where it was sold as pigeon feed) and transformed Hoekert’s orange, blue, and red-painted houseboat into Amsterdam’s first floating ganja garden. From stem to stern, the Raven’s decks were soon covered with thousands of seedlings, planted in everything from coffee cans and old shoes to garbage pails and baby carriages. Christening their new venture the Lowlands Weed Company, the duo registered at the Amsterdam Chamber of Commerce with Hoekert as the company’s director and Grootveld as its advisor.

With their new business established, they then began selling plants and packets of seeds from the boat for just one guilder each. They even put up a big sign that read "45,000 marijuana plants for sale," despite the fact that were docked directly across from a police station. Granted, the weed they were selling wasn’t the kind of skunky sinsemilla we’re used to today—these were hemp plants with barely any THC, not really suitable for smoking (the good stuff was secretly being sold from the boat of Kees’ American friend “Mickey Mouse” just down the street). But their scheme was never about profit—in fact, they claimed their business plan was actually to put themselves out of business. Rather, the whole enterprise was meant purely as a symbolic political act, with two main goals in mind: to educate people about growing their own marijuana at home rather than buying it from dealers, and to challenge the existing cannabis laws by goading police into putting them on trial; they succeeded on both counts.

After receiving a string of civil summonses, Hoekert was eventually called into a court hearing. Unfortunately, there isn’t much information available about his trial, but the case seems to have centered around the question of whether or not he dried his plants. Since Holland’s Opium Act (their version of the Controlled Substances Act) forbade only the sale of dried cannabis leaves, he claimed that the selling of live plants and seeds didn't technically violate the law. Moreover, he contended that the law itself was unjust because marijuana should never have been lumped in under the same category as heroin in the first place.

Hoekert insisted on representing himself and naturally turned the proceedings into an absurdist, Provo-style happening. Allegedly, a court reporter stated that Hoekert was "gesturing like an over-acting opera singer, sometimes behind the suspect gate, sometimes he took the place of counsel, pacing through the courtroom now and then." Among the witnesses he reportedly called was a stuffed dog, as well as two expert witnesses with the unbelievable but apparently real names of Dr. De Wied (of weed) and Dr. Hennephof (hemp court).

Ultimately, it seems the court was unable to come to a decision regarding the proper punishment, if any, for possession of hemp plants and referred the case back to the examining magistrate for further investigation and the case essentially fizzled out. Hoekert never faced more than a 250-guilder fine and a three-week suspended prison sentence. Other than that, the police pretty much left the pot provocateurs alone. Kees and Jasper had achieved their desired result: the police’s hands-off attitude led the public to conclude that growing marijuana must now be permitted in the Netherlands, and The Lowlands Weed Company effectively became the country’s first legally sanctioned cannabis merchants. As the first issue of former Provo Roel van Duyn’s new newspaper 'De Kabouter Kolonel' (The Leprechaun Colonel) reported in 1971:

“Despite the Opium Act, a few kilos of marijuana of surprising quality were harvested in Amsterdam this year. The LWC has proven with this crop, which it has largely planted itself, that a consistent application of the Opium Law with regard to marijuana is impossible. The enhancement of our country has thus been reduced to a simple matter of time. The hemp consumer has taken the law into his own hands and is sowing his marijuana himself.”

Over the next few years, Hoekert expanded and improved his gardens—growing huge bushes of weed using seeds he imported from America, Indonesia, Morocco, and other various locations. As the international press began covering the story, the White Raven became the city’s cannabis center. People from all over the world started flocking there in droves to purchase their plants and seeds. Foreign visitors were allowed to buy up to 23 plants, while locals were limited to five or ten per visit. In addition, most visitors were invited below deck for a smoke, a cup of marijuana tea, and some grow advice or political ponderings from LWC’s now-infamous proprietors. The Raven became such a tourist attraction, in fact, that a popular hippie tour called the Magic Bus even began stopping there twice a day to offer its patrons “high tea.”

This bohemian cannabis teahouse model Hoekert created was the prototype for the hundreds of coffeeshops that would soon follow. More importantly, though, the legal precedent set by the Lowlands Weed Company would serve as the foundation for the government’s policy of cannabis tolerance in the decades to come.

EPILOGUE

Jasper Grootveld passed away just nine months before I met Kees. Hundreds gathered at the site of his old protests in Spui Square to celebrate the life and legacy of Amsterdam's counterculture icon.

Sadly, in the years following our interview, Hoekert descended into alcoholism and dementia. After a medical emergency in September 2011, he spent several weeks in the hospital before being transferred to a psychiatric clinic in his hometown of Nunspeet, then to a nursing home in Elburg. There, he spent the remainder of his days until passing away on New Years' Eve in 2017. Though his death was not commemorated with the same level of fanfare as his old compatriot's, his legacy as the undisputed "Grandfather of Nederwiet" shall never be forgotten.

COMING SOON: PART 2 — RISE OF THE COFFEESHOPS

To hear more about the Provos and the Lowlands Weed Company listen to Episode 12 of our Cannthropology podcast.

Comments